Source: jdurham

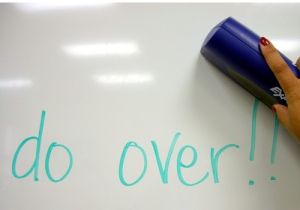

We learn from our mistakes, right? Error brings knowledge, and knowledge is valuable. Therefore, error is valuable!

Why are people so afraid of making mistakes?

- Afraid of what people will think;

- Do not want to face the consequences;

- Imagine the worst that can happen and want to prevent it;

- Do not want to disappoint;

- etc.

Ground rule

It’s important to value errors, especially inside a team, and it should be a ground rule right from the start. By doing so, teammates will feel better overall when they are working, and when they make a mistake, they will be able to concentrate on how to fix it, and prevent it in the future instead of focusing on what the team will think of them. The result is a team that works together instead of pointing fingers.

Make it clear

It’s important to clarify what’s expected of the team towards mistakes. For example, some errors may be caused by taking risks, taking those risks may be outside what’s tolerated amongst the team; we want to accept mistakes but we want to avoid people taking unnecessary risks. Here, the rule could be simply that before taking that risk, it must be discussed and if the team decides to take the risk, the mistake will be shared with the whole team.

Lessons learned

Those mistakes may be tiny, but may also have a large impact. The knowledge gained from that mistake becomes a lesson learned out of your project, and it’s important to communicate it to the whole team and other colleagues that may face the same problem, you may save them tons of time (and money!).

It’s important when discussing lessons learned that you focus on :

- why it happened

- what was done to fix it

- what must be done in the future to prevent it

Also, avoid pointing fingers at all cost, talking about it must make everyone feel like they learned something and not that they messed up (that’s the hard part).

A simple way of preventing accusations is always talking about what the team did and not what one person did in particular. For example, instead of ‘Joe used a new script that created a bug’, we could say ‘We used a new script that created a bug’. Simple!

Practice makes perfect

It may seem hard at first to look at an error as a good thing, even more to have the whole team thinking like that, but as each project is done and mistakes are made, if the focus is on the knowledge gained and the team are working together to fix errors, then people will be more and more comfortable and will work even better together.

In conclusion, accept mistakes

For many of you, it’s going to be hard, but work on it. Mistakes are alright, accept them, learn from them, and the knowledge you will gain will help you grow in all aspects of your life. People will notice more how to get up after a fall than the fall itself!

Any stories to stare? Don’t hesitate!

June 4, 2013 at 12:49 pm

Taking into account your whole article, I’ve got a beef with saying “We did this” instead of “Joe did this”.

In a team environment which sincerely acknowledges and accepts well-intended errors, team members should not be afraid of taking responsibility for their mistakes. Attributing faults at the team as a whole can make it very easy for some persons to deny their part in the problem.

Therefore, I think what should be heard most often isn’t “We did it” nor “Joe did it”, but instead “I did it”. In return, all you’ve written about should be applied and end up in a positive learning experience.

June 4, 2013 at 2:08 pm

I apologize if my sentence could be interpreted as attributing fault to the whole team, as it was more intended to suggest how you communicate with the team to avoid pointing fingers risk making people feel bad.

The error should be discussed, but to avoid negative feelings towards someone, using “We” instead of “You” helps a lot.

Team members should in fact acknowledge the fact that they made an error, and some may very well “dodge the bullet”. In that case, I still suggest sticking with the “We”, but it is important to have a one-on-one talk with the member to hear his side, and then explain the team’s side.

Also keeping in mind, even if the team accepts errors, anyone really committed to the team/project will automatically feel bad about the mistake, by avoiding the “he did it” and “I did it”, you lessen this negative feeling and can actually make him feel better.

I hope that clarifies!

June 19, 2013 at 10:48 am

Seems my WordPress dashboard doesn’t warn me when my comments are replied to; I’ll have to find a way to fix that.

I do understand your point, although I disagree on the notion of automatically feeling resent, guilt or any negative emotion from a self-acknowledged mistake. As you wrote it yourself, “it’s important to value errors”; if a team gives value to mistakes, then I fail to understand why any negative impact should be felt by its members.

Consider a scenario in which a team member acknowledges he forgot a critical step in the middle of an application’s deployment. In this case, the mistake is factually caused by that person not having double-checked his progress in the procedure he was following. Stating as a team “we did not properly validate the deployment artifacts during the process last Friday” is constructive behavior indeed, but it doesn’t precisely address the problem. In fact, the person at fault might even feel he didn’t have that much of a responsibiltiy in the incident since it was “the team” that didn’t properly validate his own individual work. Perhaps someone will suggest “the team” writes down a step-by-step deployment procedure, which might be done “someday” if that “special someone” finds the motivation and effort to do so between two seemingly-way-more-important tasks.

Alternatively, the team can state “Bob didn’t validate the deployment artifacts during the process last Friday”. In a constructing and learning-prone environment, it would be easy for one of Bob’s coworker or even Bob himself to raise his hand and suggest he makes good use of his deployment expertise and writes down a clear, step-by-step procedure he or any other team member can follow for the next deployment. From that precise acknowledgement, the responsibility of mitigating the risk of future deployment errors will clearly be on Bob first while still being embraced as a team-level issue. Bob will also feel empowered from his learning and will feel he has done something to improve the team’s efficiency and flexibility.

Note that in the second outcome of my scenario, nobody explicitely blamed Bob for his mistake or said anything to make him feel bad about the situation simply because none of that was necessary for the situation to be resolved. Now, if some team members had committed such behaviors, that would be evidence of a negative work attitude from them, which is a problem in itself.

TL;DR: a team in which its members acknowledge openly their responsibility about mistakes can use its collective expertise to offer them solutions for improvement and empower them as problem-solvers.

June 20, 2013 at 10:00 am

I do agree with you that being opened addresses more directly the situation itself, and I’m all for direct/open; but for many, even a self-acknowledged mistake will make them feel bad, and their reaction during the meeting may vary from neutral to storming out. What’s important here is to know your team members, if everyone is alright with the direct approach, then go right ahead! Don’t get me wrong, it doesn’t mean that if people are more fragile, that you shouldn’t address their errors, just be careful on how you do it; if something is problematic, talk to them one-on-one instead.

As for your example of someone suggesting writing procedures when a critical step was forgotten, well it goes to show you that maybe the procedures were not clear, maybe someone was supposed to double-check his work and didn’t, or something else. In the end, it may be easier to point only one member, but the whole team (or a part of it) may actually be responsible at the core of things. Assigning someone to write up procedures for the next week may be a great solution here, and everyone can then follow a clear checklist for deployment. However, if you keep your focus on “Bob”, than your solution may end up being that “Bob must be careful next time” or “Someone will have to double-check Bob’s work” instead, which will not be as efficient, Bob will feel awful which brings nothing constructive to the team, and the problem may rise again with someone else.

It is good to mention that even if “we” is used during meetings, the person responsible will know he made the mistake; if he doesn’t, than, as mentioned above, maybe there is something wrong elsewhere, and it’s important for him to share his view. Maybe he really cannot take responsibility for his acts, and that should be addressed one-on-one with him.

Those are of course all examples and speculations, the main idea here is to focus on how the team can improve, and communicate constructively, avoiding to make anyone feel bad which will reduce their motivation and commitment to the team, making matters worst. Having had different supervisors with extremely different ways of “leading”, I can assure you that you are more motivated to follow the one who avoids pointing fingers, and you respect him more.